Speaking from the bench of her Long Beach courtroom, Superior Court Judge Judith L. Meyer did not pull punches as she bluntly described two Long Beach homicide detectives.

“The behavior of the detectives is appalling and unethical and inappropriate,” she said after attorneys accused the officers of coaching one witness during a photo line-up and misspelling the name of another in the lead-up to a murder case.

So on the eve of trial in 2017, Meyer blocked the district attorney’s office from introducing key evidence in its case. Within minutes, prosecutors informed the judge that, for now, they could not press ahead against the accused killer of a 23-year-old gunned down outside his Central Long Beach apartment.

The defendant was set free. The victim’s mother was left stunned: “I never got any explanations,” she said.

But behind closed doors, the case devolved into finger-pointing, recriminations and surprising admissions of mistakes.

Eleven months after her broadside against detectives Malcolm Evans and Todd Johnson—and after a private visit from Long Beach police—the judge retracted her criticisms in two unusual letters addressed to Police Chief Robert Luna.

In the first one, a draft of which Meyer emailed directly to the detectives, she not only vouched for their integrity but hinted that she had erred in the ruling that lead to the dismissal of the murder charges. She spent most of the second letter defending her own integrity.

Now, Meyer’s extraordinary actions have set in motion a chain of events that has spilled into yet another case handled by the same two detectives—this one of an allegedly corrupt Long Beach police officer accused of leaking confidential information to a suspected gang member.

That officer’s lawyer, Case Barnett, said he believes the detectives and their superiors attempted to intimidate Meyer to protect their reputations and guard against other cases being adversely affected by her on-the-record critique of their ethics. Barnett, who obtained the two letters from the district attorney’s office through discovery, said he wants to question the judge under oath.

“They basically went into the judge’s chambers with documents in their hands to try to convince her that she made a mistake, and they did this in order to save their credibility,” Barnett said of Long Beach police. “Why would you do it in this fashion if not to intimidate? This speaks to the level they will go to protect themselves.”

Barnett said he also plans to file a motion to have the corruption trial moved out of the jurisdiction of the Los Angeles County Superior Court, arguing the entire bench could be tainted.

Police officials, for their part, deny any improprieties. They say the detectives’ supervisors met with the judge to “identify if there had been any misconduct by the detectives that would warrant an internal investigation.” They said they found no reason to take action against the officers.

“No one wants to take responsibility for what they’ve done,” the victim’s mother, Christina Davis, said. “It’s unfair. It’s unfair to my family, his friends, everybody. It’s just unfair.”

A judge goes on the defensive

Meyer, who has been on the Superior Court bench since 2006, has a reputation for being talkative and familiar as she presides over her Long Beach courtroom. Sometimes, she might pounce when other jurists might ponder, according to lawyers and law enforcement officials who’ve watched her over the years.

In her courtroom earlier this month, she drew laughs from jurors when she gently teased an attorney who mimicked an automated voice played from a police recording during closing arguments for another murder trial.

After court had adjourned for the afternoon, however, Meyer was more subdued when a Long Beach Post reporter asked her about the two letters. She said they’d gotten her “in enough trouble already” and then politely maneuvered back to the bench.

With Meyer and other participants saying little about the circumstances surrounding the letters, a number of key questions remain unanswered, most notably: What prompted the judge to write her missives? Did she write them at the behest of the police? What was their purpose? And what, if any, repercussions did Meyer confront at the courthouse, where other parties—even the victim’s family—were kept in the dark?

Although Meyer isn’t commenting beyond alluding to the “trouble,” her second letter suggests she came under criticism after she sent a draft of her earlier letter to detectives, which they shared with Chief Luna without the judge’s knowledge.

In that first letter, Meyer had praised the detectives as “meticulous,” “ethical,” “credible” and “prepared.” She said that the witness-coaching allegation by the defense, for example, “was an unfortunate misunderstanding,” not misconduct.

She went on to acknowledge that other issues she blamed on detectives had, in fact, been previously addressed at a preliminary hearing over which she presided, including an allegation that police misspelled an informant’s name to conceal from the defense his connection to a robbery.

“I find it unfortunate that the information to exonerate these officers was readily available to me, and I did not catch it,” Meyer conceded.

She noted that because the district attorney’s office did not dispute the misconduct allegations and did not call the detectives to the stand to rebut them, she was forced to rely on the incomplete information presented to her on the eve of trial.

“It is unfortunate the train of events which transpired,” the judge said in the first letter, dated April 23, 2018.

It was also unfortunate, the judge would soon lament, that her letter even got out.

About a month later, in the second letter, she insisted nobody but the detectives should have known about the draft. Within an hour of emailing it, Meyer said, she told them she was not going to send a finalized version because “as a neutral party to this entire affair I should not express any opinions.”

By then, it was too late. Not only had the detectives shared it with Chief Luna, but the district attorney’s office eventually also received a copy. Although Meyer does not provide specifics about what happened next, her letter suggests there were repercussions.

Among other things, Meyer wrote, the draft created “some issues and misunderstandings.”

“It was communicated to me that this [earlier] letter gives the implication that I have a relationship with these officers and find them to be generally honest. I would like to clarify that I have no relationship with these officers. … I never intended to give a representation that I have an overall feeling about their general character.”

She concluded by saying she wanted “to dispel any concerns anyone may have about my integrity. It distresses me greatly to think anyone considers me unfair or biased. I strive for a reputation of being fair and unbiased, and more importantly, if shown an error of my ways, to consider that as well.”

Lawrence Rosenthal, a Chapman University law professor and former federal prosecutor, said the judge’s critical error in this case was to have met privately with the police to discuss issues central to the dismissal of a murder charge.

“She shouldn’t have written the first or the second letter because it’s not her job in an extrajudicial proceeding in which you don’t have all the parties present to reach a conclusion,” Rosenthal said. “She should confine her findings to the ones she’s supposed to make in open court.”

Rosenthal predicted that the meeting and subsequent letters could potentially compromise other cases involving the two detectives.

“Once you have members of law enforcement who are compromised,” Rosenthal said, “it jeopardizes every case they touch.”

Although both detectives are still on the force, Johnson has been transferred out of the homicide unit, according to the department, which declined to provide further details.

A Mother’s Grief and Frustration

Davis lost her son in September 2010. Now, almost 10 years later, she’s losing faith in a criminal justice system she believed would hold someone accountable for the killing.

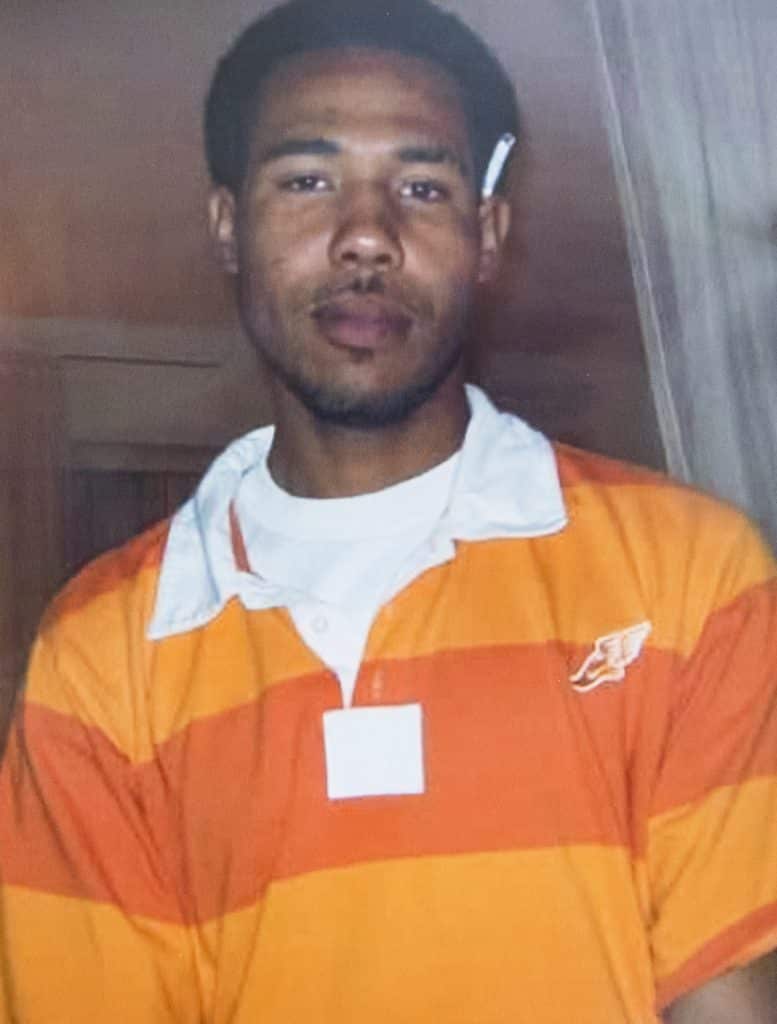

Her son, Brian Humphries, was outside his Long Beach apartment waiting for his mom to arrive after work when at least two people got out of an SUV and shot him at close range, according to witness accounts. It wasn’t until six years later—an eternity to the grieving mother—that an arrest was made and charges were brought against 24-year-old Daniel Delatorre.

Although no motive was ever publicly disclosed, a Long Beach police officer suggested during a preliminary hearing that a Latino gang allegedly tied to the killing sometimes targeted black men for no other reason than the color of their skin.

Davis and her family said they’re unaware of any connection between Humphries and Delatorre or any gang. On the contrary, they said, Humphries was working as a security guard trying to build a life for himself.

Delatorre’s trial was just days from opening when the questions surfaced in court about the conduct of the two detectives, setting the stage for the dismissal of the case. Davis says no one—neither the police nor the prosecutors—ever explained to her why Delatorre had been set free.

Nor had anyone told her about the letters in which the judge backtracked on her condemnation of the officers and suggested that she may have erred in preventing prosecutors from introducing key evidence, essentially forcing them to drop the charges.

In the living room of her home, reading the two letters for the first time, Davis’ frustration boiled over.

“It’s just a whole big old screw up and this guy is walking free,” she said. “It’s the bottom line. He’s walking free living his life because of the ignorance of the court. This is ridiculous.”

She said she doesn’t know where the case stands today. The matter remains with the district attorney’s office, which will say only that the investigation is still in progress.

The uncertainty has added to Davis’ grief.

“It changes you a lot, mentally, physically,” she said. “To know that the person is still walking around, it’s even harder. It hurts.”